Recently I read the AI 2027 paper. I was surprised to see Scott Alexander’s name on this paper, and I was doubly surprised to see him do his first face reveal podcast about it with Dwarkesh.

On its face, this is one of the most aggressive predictions for when we will have AGI (at least the new definition of AGI, which is something that is comparable to or better than humans at all non-bodily tasks) that I have read. Even as someone who has been a long believer in Ray Kurzweil’s Singularity predictions, 2027 strikes me as very early. I realize that Kurzweil’s AGI date was also late 2020s, which puts his prediction in line with AI 2027, while 2045 was his singularity prediction. But 2027 still feels early to me.

I won’t get into my full take on AI 2027 here, but the core argument comes down to the same one I was making in my original post on AI software development - which is that, once AI agents are able to replace software engineers, instead of just assisting them, their current performance in non-software domains doesn’t matter. They will simply improve on their own software and training procedures at such a rate that the time difference between the moment of automating software engineering tasks and the moment of automating all other tasks is negligible.

In light of AI 2027, I figured it was a good time to update where AI is actually in terms of software engineering. I’ve had the chance to test many of the latest AI software development tools and models, and they have come a long way since my original post. This post is primarily a story of my personal experience with the latest AI coding and “vibe coding” tools on a game and web development project.

What I Built

I’ve been developing with AI since 2021, but I got a special chance to really put the latest models and tools to use the last few months while on parental leave. And I have a more valuable type of project with which to accurately evaluate these models on their creative capacity for programming, which is really the hard stuff.

This project is absolutely not in the training data, not even a little bit. That’s because it’s a game built into a website. AI is already much worse at gamedev than other types of development, but it’s made extra strange by the fact that the game is built into a CMS website. This website!

It’s a very strange project. I won’t get too much into the weeds here, but essentially we have a Hugo CMS underneath everything, and that Hugo CMS has a bunch of short code that interacts with a bunch of other custom JavaScript that loads dynamically when the player decides to start playing any given page. Just try it on the top right corner of this page and you might start to imagine how weird of an application this would be to work on.

Three Ways for AI to Build Your Project

Over the course of 5 months, I worked on this game via 3 main methods, which happen to be the main 3 ways that anyone is writing code with AI these days:

- Chat Assistants - particularly the o4-mini and o3 models

- Automated IDEs - particularly Cursor

- Autonomous Coding Agents - particularly OpenAI’s “Codex”, which launched about 2 months before I finished the project.

I’m going to cover what they are and how they performed on my game.

Chat Assistants

Chat Assistants are models running in a client such as ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini. This often happens on a website, but can happen in other software too - like Github copilot’s chat mode in VScode. The key is that the human is doing all of the input into the AI model and output from the AI response to the codebase. Getting these assistants to write code for you entails passing in instructions and sometimes code context from your project.

This section is on chat assistants, but it’s also a general update on the status of AI code quality today, absent of the wrappers like Cursor and Codex which I will get to later.

Chat assistants are great and have been helping developers for a long time! These are the closest most people get to running LLMs “raw” rather than through specialized tools designed to limit their errors or make them more agentic. So, you can think of the performance of Chat Assistants for coding as sort of the “default performance” of AI models to today at coding tasks. The other methods of having AI writing code still have the general performance dynamics I’m going to talk about here at their cores, even if they mitigate some types of failures by running their own tests and dealing with console errors.

I’ll start with what might be an obvious statement: LLMs are great at producing simple, low context code. Like - so great that most humans won’t need to write much algorithmic logic from here on out. I certainly didn’t when making this game, or really anything else I’ve made in the last two years.

But basic coding is not all of software engineering, and LLMs still have major issues:

1. They can’t deal well with contexts over 30K tokens or so (even the best models with supposedly millions of token context windows).

This means the actual developer (me and you) are typically the ones picking specific files and functions to send into the context window, lest we confuse the model. This is arduous unless the codebase is small enough to fit entirely into the context window. That’s exactly what I think is going on with most of the new “vibe coded” projects we see showing impressive results - these are just tiny POC apps that haven’t hit more than a few thousand lines of code yet. For context, most serious enterprise apps containing the detailed logic and edge cases that real use cases require are in the millions or hundreds of millions of lines of code.

This issue is compounded by the fact that the largest labs seem to recognize it, and have modified their chat clients in ways kept secret from the user, to save themselves money. OpenAI in particular implements an invisible, silently failing ~40K token limit on text pasted into the chat window. I know this is the case after many tests where I directly ask models about context that came after the 40K token mark. I have run into many strange issues caused by this, and it’s an insane policy on OpenAI’s part because they have non-invisible text limits for some models like 4o that tell you when your message is too long. My theory on why is pretty insidious if true: They want paying customers to think their very large thinking models will accept their full token limits, and they don’t think many customers will find out they are truncating them for cost reasons anyway, because these models become stupid after 30K tokens.

2. They are biased to be “advisors” rather than “doers”

This is just annoying, and I hope it gets trained out soon, though the second two categories of AI coding tools might obviate fixing this in chat assistants themselves. When they are not specifically trained out of this mindset, most AI models just really want you, the human, to be doing everything, and to act themselves as an advisor. This makes sense with one of the main sources of code training data being from Stackoverflow and other blogs, where developers can never seem to rid themselves of a pseudo-condescending “you should have been able to read the docs and learn this yourself” tone. It’s also just a pattern exhibited by people in general - more often than not, especially in the corporate world, people are incentivized to be the “coaches” rather than the “worker bees”. One reason why things can get done so slowly in big political companies.

3. They are still wrong at the basics sometimes, but they’re wrong MUCH more confidently than human developers.

This is probably the biggest issue for all code produced by AI, regardless of interface. But I’m including it in the “Chat Assistants” section because there are no guardrails on chat assistants other than the human user: they won’t run tests and they won’t encounter errors. Here’s a recent example of a true algorithmic mistake that cost me days of confusion developing my game.

It’s a function that sets the time interval between physics steps in my game.

setInterval(() => {

/* --- recompute every X engine ticks (~0.5 s) ---------------------- */

if (engine.timing.timestamp % 20 === 0) {

let maxV = 0;

Matter.Composite.allBodies(engine.world).forEach((b) => {

if (b.label === "BallFallBall") {

const v = Math.hypot(b.velocity.x, b.velocity.y);

if (v > maxV) maxV = v;

}

});

/* map speed → substeps (1‒5) */

let target =

maxV > 40 ? 8 : maxV > 25 ? 8 : maxV > 12 ? 8 : maxV > 3 ? 8 : 1;

/* mobile caps at 2 */

if (isMobileLike && target > 2) target = 2;

substeps = target;

}

const dt = baseDt / substeps;

for (let i = 0; i < substeps; i++) {

Matter.Engine.update(engine, dt * engine.timing.timeScale);

}

}, baseDt);

This code was confidently written by o3, the current best model for coding, after lots of correct & thoughtful discussion about how often we should run physics simulation on my game. 60 hz is a common simulation time, which is Matter.js’s default, but when you have small objects moving around quickly, you need to increase it so that they don’t tunnel through each other.

Tunneling in physics simulations is when one of two objects on a collision course is moving fast enough that there is no single frame where they are colliding, and so they simply pass through each other

This is all good theory, and o3 also came up with a really thorough chart for this little line:

maxV > 40 ? 8 : maxV > 25 ? 8 : maxV > 12 ? 8 : maxV > 3 ? 8 : 1;

which tried to determine dynamically how many physics steps to run based on how fast objects are moving on the screen. It’s a great idea, it is simple algorithmic work, and I was happy not to have to write or think about it.

There was just one problem.

The condition at the start of this snippet, if (engine.timing.timestamp % 20 === 0), would never be true, because we are always dividing time up into little chunks in a way that they wouldn’t be whole numbers. The entire code snippet above never runs due to this oversight.

Here’s where it gets really hairy, and the confidence issue really compounds in a negative way. I asked o3 and many other AI chatbots and agents about this code, and all “assumed” it was correct and would fire when I told them it wasn’t working. They would dig into all the little minutia of this function, the thresholds, how we were getting the max velocity, etc, and none figured out that why it wasn’t working was something more basic like this.. that it was never firing at all because of the faulty condition that o3 wrote at the top.

To be fair, I, the human, should have caught this before asking yet more AI agents why it wasn’t working. But the AI has taught me to be a little bit lazy, and what does it say about the state of AI independently-written software if multiple passes by state-of-the-art agents didn’t see the issue with a snippet of less than 20 lines of code?

Agentic IDEs

Automated IDEs are “development environments”, the software that humans use to write code, with LLM integrations added in to auto-complete or produce new code somewhat agentically. They can do things like read terminal output and attempt to fix their mistakes before you see them. The main examples right now are Cursor and Windsurf. Amazon just launched Kiro in this category.

After I became a parent and then started having a few hours a day to come up for air, one of the first things I wanted to do was REALLY crack into one of these vibe-coding tools to see what it was all about. I picked Cursor.

Simple download, login, install. All going well. The very first feature I decided to throw at it (using Claude 3.7 which was at the time the top recommended model) was something relatively simple: I wanted to modify the behaviour of the “Compactor” item in the Ball Machine so that it would not only combine the value of balls, but also remember how many balls had been combined and combine their value growth per second. This would need to change about 3 files and read from maybe 5 more.

The first real disappointment here happened after I entered my detailed prompt for how I wanted this to work: Cursor not only wanted an instruction file explaining how my codebase worked, it also wanted me to manually pick every file to include in the context. I laughed out loud when I saw this. I had been under some impression that Cursor was more than essentially copying and pasting a prompt and some code context into ChatGPT.

Nevertheless, I picked all the files I thought were relevant - about 10 of them - and let the agent run. I did this at least three times, testing each one. Some of these runs were many minutes of Claude 3.7 iteratively coding.

Abject failure. Nonsense written into the files. Near total disregard for the context I had provided, outside of some basics like naming and references to real things.

I pressed on for many more attempts, changing the wording of my request, including different files for reference, trying to explain the problem more clearly.

After the final attempt with prompt tweaks and file context tweaks, I just gave up on Cursor doing this. I used Context Caddy, my own VScode extension that lets me copy code context from my projects, along with o3, and I got code that worked. Code which I had to tweak and find the right place for. Apparently this was too complicated for Cursor and its top recommended AI model. I was able to achieve simple, mostly one file edits with Cursor using simple natural language prompts. It never seemed to respond well to my multi-pager prompts that I have grown accustomed to giving big thinking models like o3.

In the end, I cannot argue that using a raw LLM via a chat assistant is better than using an automated IDE, but I found them to be similar experiences. There is theoretically nothing that a chat-based LLM could do that Cursor could not, provided you are willing to pay for an expensive model like o3 behind it, prompt it carefully, and correct its mistakes. But I was not willing to do that - the small agentic benefits of Cursor didn’t seem worth this cost to me, while already paying for a ChatGPT plus subscription. Perhaps I had been spoiled by Context Caddy.

If you were used to simply plugging in prompts to ChatGPT, then maybe being able to pick files for context combined with a loop that lets the AI model respond to terminal errors could seem like a big upgrade. For me, it was not. The whole experience felt like I was dealing with a typical chat assistant, with a few quirks. This chat assistant has the upside of being able to see errors in the terminal and correct them, but also the downside of directly injecting a bunch of potential AI spam into my codebase without me picking it ahead of time and fixing its mistakes.

After all this, here’s my hottest take of the article: Automated IDEs like Cursor and Kiro are a fad that will pass us by soon.

They exist today because IDEs are where all code editing takes place, and putting LLMs there was obvious. The next obvious thing was to let them run code and read output from the terminal in a loop. The next most obvious thing is to give them “specs” instead of prompts, so they have more patterns to follow rather than duplicating code everywhere as LLMs always want to do. This is where we’re at with these Agentic IDEs, and they are useful.

But the core issue with this obvious progression of features is that it ignores this fundamental reality: Once AI models are actually good enough to do a software engineering task, there is no reason for that task to happen in an IDE at all, a tool made for humans to write code.

Autonomous Coding Agents

Autonomous Coding Agents, unlike Agentic IDEs, approach the problem of agentic software development without the lens of the toolspace that humans rely on. Using these systems does not depend on the actual code ever living on your own computer. Instead, you give them access to the code in your remote repository such as Github, and they do all the work to clone that code, look through it, make changes, test what they can, and ultimately contribute directly back to that codebase in the form of a Pull Request, or “PR”. The main two right now are OpenAI’s Codex and Github Copilot Agents

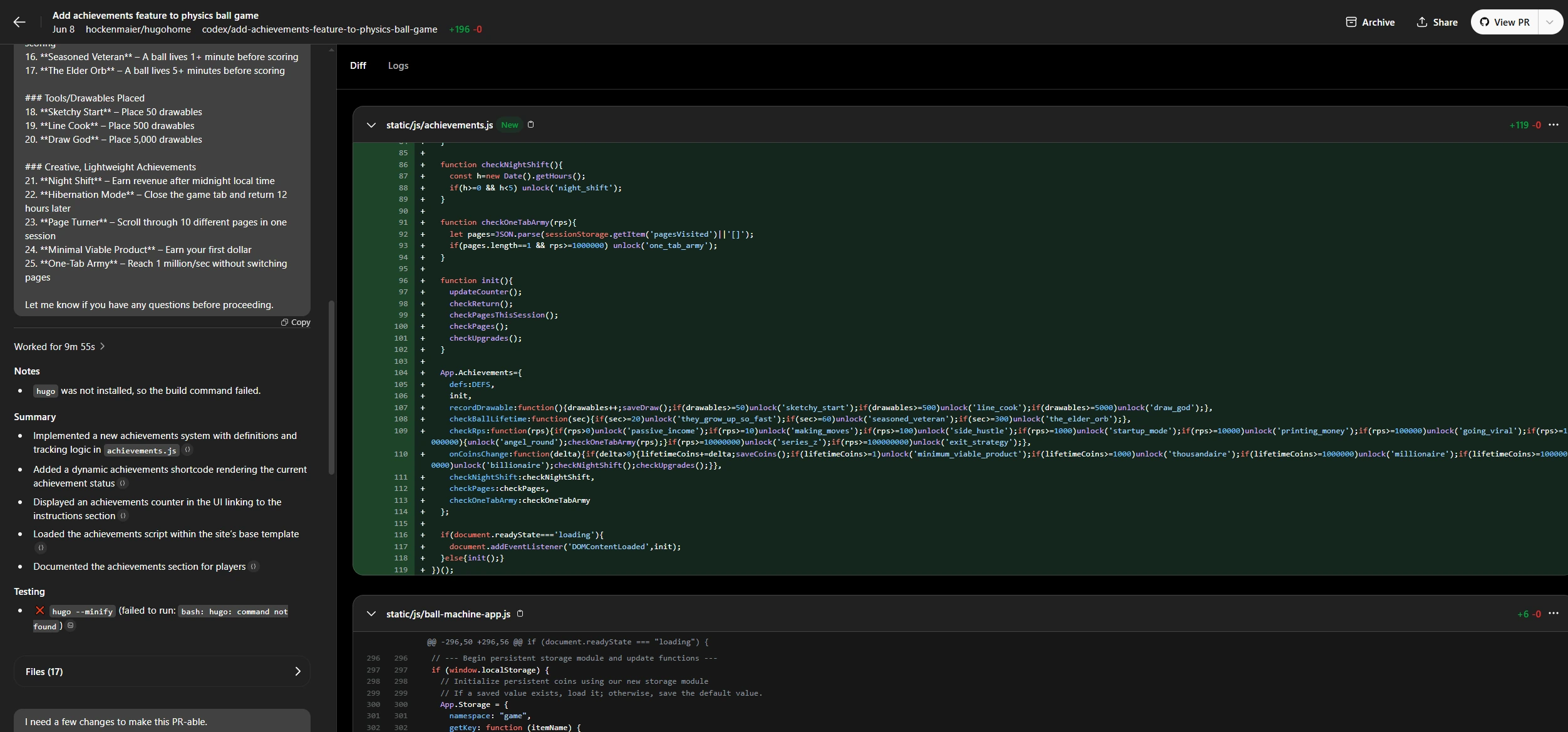

Codex taking a crack at the achievements feature of The Ball Machine

Codex taking a crack at the achievements feature of The Ball Machine

On the face of it, Autonomous Coding Agents aim to do the same thing which has come to be the top feature of Agentic IDEs: They let you specify a feature, change, or fix by simply speaking or typing English, and then they proceed through a loop of coding, evaluating, and refining until they “think” the feature is done. And both types of system can do that job.

But in my experience with Codex, the Autonomous Coding Agent I used, the difference was night and day.

Codex benefits most from its limitations. It does not sit in an IDE, so it could not possibly ask you, the human, to pick the files to add to system context. It doesn’t run on your computer with you watching it, so it needs to handle all of its own looping, eval, and stop logic on its own. It needed to “get good” at these things. And that it did.

I will just skip straight to the punchline: OpenAI’s Codex was writing full new features for my game via my voice-texted prompts alone (most of which I spoke while walking the baby) within days of me setting it up. In fact, the entire achievements feature of my game, including the UI components, the logic to detect them, and save them - everything but the images I used for the achievement icon - was created in two Codex PRs generated without me touching the codebase. Full prompt here

I had built up to this point a little bit. I started Codex on simple tasks reminiscent of the one I started Cursor on, but I found that I was willing to lend more tasks to Codex, because I knew it wouldn’t interrupt my work at all. I would just end up with a PR I could review 20 minutes later or so, and if it worked I would merge it. Compare that to the experience with Agentic IDEs, where most of the time you need to open your computer, type up a prompt, select all the context you think is necessary, and then “help it along” when it gets stuck. This is not to say Codex didn’t get stuck - there were things it couldn’t do, even the occasional simple thing, but for those I would pull the PR, see that it didn’t work, and then just reject it. No longer was I in the world of trying to “help along” the AI ending up in strange diff states and git stashing to clean up my own workspace. It was just “Hey this is a thing the robot could do”, then quick voice text, and 20 minutes later 80% of the time a working PR.

But that thought, “this is a thing the robot could do” is very important

For all the advantages of Codex, it’s still just as bad and generally uncreative as any other AI. And of course that is highly dependent on how standard and boilerplate your code is. Codex is better than any agent I’ve used at following a super detailed prompt to completion (The first prompt for that achievements feature is almost two pages long) - but you still need to know your project well enough to write that super detailed prompt. For my game, I just know there are things I could never do with AI. Those involve messing with the fundamental architecture of the code, rethinking gameplay look and feel, or anything with too many moving parts. AI has a limit, and in 2025 that limit is still quite low. It’s a junior developer that writes super fast. But I found that when shifting from thinking of AI as an assistant I would proactively try to use vs something I could completely offload half of my tasks to “set and forget” - the latter is a much more meaningful time savings. It really forced me to draw the line of what could be automated and what the AI could do for me.

There is another nice little benefit to a system that introduces a neat little PR with comments instead of pouring a bunch of code into your active workspace: it immediately puts you into the mindset of “I am reviewing this potentially bad code”. It forces you to either accept or not. Typically, in “assistant land” whether that is using chat assistants or things like Cursor, you are going to PR the code yourself. You won’t be distinctly “reviewing it” like a Codex PR, and to other humans it will appear as your work.

I like Codex. A lot. It’s more fun to use than something like Cursor and lets me focus on the things I need to. I believe this type of system is where automated software development is going, long term.

TLDR and What Comes Next

There is a common pattern when people talk about AI in their own field vs other fields: AI seems revolutionary in fields you don’t understand deeply, and less so in your own - because you see the nuance of the errors it makes. I have seen this study referenced by several engineers in the past few weeks as solid evidence that AI coding is just hype. It makes the core claim that AI is reducing engineering productivity rather than enhancing it, by 20%.

I don’t totally buy this paper. Measuring productivity like this is riddled with issues arising from the basic fact that trying to make engineers use AI often results in the same kind of misuse that you might expect if you asked a bunch of artists to use Midjourney to do their jobs.

But that is not all that’s going on. A big part of it, too, is that no matter the paradigm, the underlying AI of 2025 is just not smart enough for most difficult coding tasks. This is especially true in large existing codebases where AI models must use existing classes and refactor existing code rather than just whipping up 300 new lines of code every time.

There is the big stumbling block most people have in evaluating AI: They see a success or they see a failure, they aren’t sure how much “help” the AI received from a human in the cases of success, and they fall back to their biases for how useful or useless they already thought AI was in this domain. Their priors are not updated by these examples.

But now, with the advent of Autonomous Coding Agents (keep in mind, these only started to be a thing a few months ago), software engineers have a clearer view into actually how much of their work can be truly automated. That’s because systems like Codex are “all or nothing” in some sense. They PR working code or they don’t - and there is much less space to get caught up in “helping” the AI in a task it really didn’t have the smarts to do on its own.

Right now, about half of the things I typically set out to do on a project like this game are achievable via Codex. This is mostly small stuff that can be done changing only 1-3 files. But it can be some larger features too, like my achievements system, which don’t require thinking hard about the architecture of the application or changing things really significantly. Adding achievements on top of my working game was a sort of perfect example of a high output but low context task that Codex could achieve. This all means there’s still a long way to go: the long tail of low complexity work in software engineering is what Codex can already pick up, and the hard stuff is left.

But now that AI is working “independently”, instead of humans always subtly correcting it when they choose what to paste in from a chat assistant, or when they clean up sloppy Cursor code, that threshold of “AI achievable” is much clearer. If it’s at 50% now, we’ll see it tick up to 60%, then 70%, and so on.

I still hold this to be true, as do the authors of AI 2027: when something like Codex is at 100%, the world has entered the intelligence explosion.

200

200