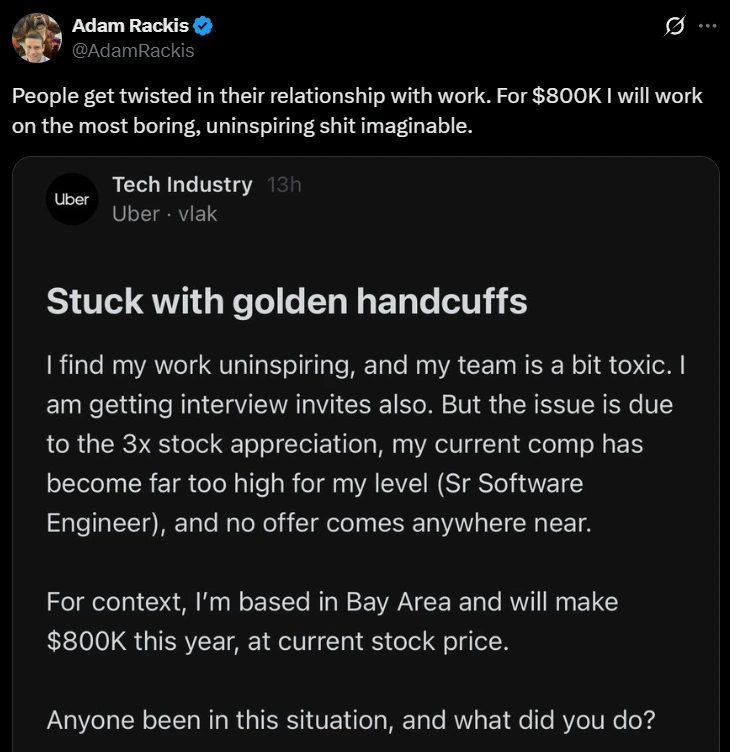

Early last year, I came across this tweet:

https://twitter.com/AdamRackis/status/1762321041899012307

The discussion was surprisingly contentious. Maybe I should stop being surprised given the state of Twitter/X and all social media, but still it’s sometimes shocking how dug-in people are in their beliefs about work. On the face of it, “people get twisted in their relationship with work” seems like a reasonable take. “Stop complaining—you are making 16x the median salary in this country. Just do the boring job with the toxic team.”

Let’s stop and think about this for a second. The original poster (OP) is making $800K annually due to the appreciation of Spotify stock. An obscene amount of money? Maybe, maybe not. I do not have the typical hang-ups about the wealthy or ultra-wealthy. I don’t see this world as a zero-sum game, and I think the richest people out there have usually done some amazing things, especially in countries like the US where most wealth is not old wealth.

But there is a huge difference in the two main routes to becoming wealthy:

- Founding a company or practice, or joining one early, out of passion - which then goes on to become incredibly valuable

- Working for someone else doing a job you think is boring in order to join the 1%.

In this article, I’m talking about the latter.

I propose this core question for this type of person engaging in number 2: Is this large income worth doing a job you find boring, or working with people you feel are toxic? I would say no. Absolutely not. OP is clearly regretting how he’s spending his time at work. He should look for something to do that he values, even if it pays a quarter as much as he gets now. Or less!

The Hedonic Treadmill

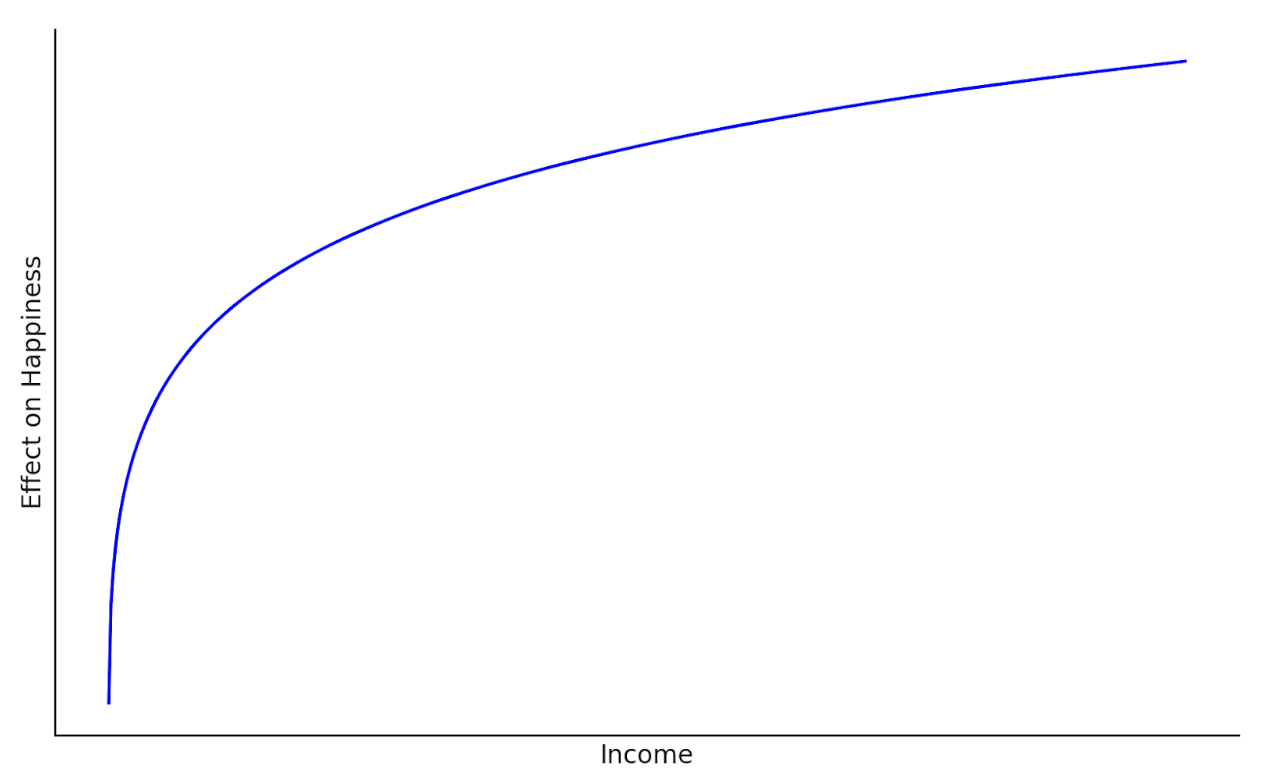

There’s an often misquoted study from ~2010 that personal income beyond about $75K (presumed to cover basic necessities with a comfortable overhead) does not lead to further happiness. This number is actually about right when it comes to simple reported happiness, which has more to do with the hedonic treadmill than anything else. But the study in question was also measuring reported “life satisfaction” as surveyed, which did not stop increasing with income. Of course, “life satisfaction” is a fraught survey metric as well, as it might actually measure a perceived comparative number with one’s neighbors (we’ll get to this later).

But whatever the proper measure of happiness or satisfaction is, there is a great deal of logic to thinking its relationship with income looks like this:

As in: there are diminishing returns to incremental income. Not a revolutionary idea. It’s obvious. But it also means that somewhere along this curve is the often-quoted $75K, and somewhere far to the right is OP’s $800K. And the curve between those points is probably pretty flat.

What could OP get in return for moving to the left along this flat section of the curve? Eight hours of time per workday, at least, that he finds incrementally more valuable. How much do you think those 8 hours could improve his life satisfaction on their own happiness/hours curve?

This is where the real paradox comes in. Gaining wealth is supposed to make your time more valuable. You choose to get more services, have a housekeeper, maybe even a private chef. But if those things actually indicate a person values their time more highly than someone poorer, how come they would even consider sacrificing most of that time doing something they find boring, or with people they find annoying? Just to maintain their position along the flat section of the curve?

Maybe they aren’t prioritizing happiness at all.

Keeping up with the Joneses

My argument so far would be absolute blasphemy to most of the $500K+ salary people who don’t have much fun at work. Let’s talk about their two most common counterarguments:

- “Work should be a sacrifice, and more money means more security for my family.”

This is noble. It’s also way too self-sacrificial for the extremely wealthy first-world people we’re talking about. You’re making $800K. There is not a salary sacrifice in the world that will make your family “insecure.”

And what pattern does this even establish? You’re going to choose to be unhappy for most of your waking hours so that you can guarantee your children will be able to do the same? What are you actually working for if not you or anyone else being able to actually enjoy themselves?

- “But I could make this crazy money and then retire in 5 years.”

Now this is a good argument! You could indeed retire in 5 years after making $800K per year and then spend your time with family or pursue passion projects! The problems here are twofold:

First, nobody does this. Instead, they spend more money. Of course, some of it will be saved, but the main thing that happens when people find themselves with far more money than needed for their family’s security is that they spend it. Bigger houses, more trips, elite schools for the kids. These make you feel well-off compared to your neighbors but don’t push you much higher on that flat curve.

Second, people find value in being useful. There’s a reason why so many struggle in retirement. Even with a rigid FIRE plan, you’ll still want to work afterward on something interesting. So why not find that now?

What’s actually happening? Lifestyle creep. I think this is 90% of why people feel they could never work on something more fun or meaningful for less money. They’ve already started to spend their new money, and now losing those things would hurt more than gaining them felt good. That damn hedonic treadmill.

What is “Enough”?

While writing this essay I came across another recent one from Adam Singer, who is more blunt about this:

https://www.hottakes.space/p/250k-per-year-is-plenty-of-income

Of course I agree, but what I found really funny while reading it is that I see two reactions to this 250K threshold: That it’s extremely high, and that it’s extremely low. These diverse reactions are only possible in a society where, for many, money has become largely about comparison to others vs something needed to live a satisfied life. I think those who see this and think 250K is extremely low to be “plenty” are living in comparison land.

So, think deeply about what you value. Money itself is a means to an end. It’s the way you spend your time, and that includes working too, that has true value. Value your own time as much as your spending habits would suggest you do. This is the right logic for your long-term well-being.

We might be approaching a technological singularity. It’s a healthy time to step back, reflect on the fundamental values driving our behavior, and make changes. Wouldn’t it feel silly to spend most of your waking hours working miserably on meaningless things, only to arrive in the second half of your life in a world of true abundance?

200

200