Vision is the last hurdle before AGI

3D Modeling · AI · Invention · Predictions · Singularity · Writing

I have long been of the mind that LLMs and their evolutions are truly thinking, and that they are on their way to solving all of the intellectual tasks that humans can solve today.

To me, it is just too uncanny that the technology that seems to have made the final jump to some degree of competence in tasks that require what is commonly understood as “thinking” or “understanding”, after a long string of attempts and architectures that fail these tasks, is a type of neural network. It would be much easier to argue away transformer models as non-thinking stochastic parrots if we had happened to have had success with any other architecture than the one that was designed to mimic our own brains and the neurons firing off to one another within them. It’s just too weird. They are shaped like us, they sound like us in a lot of ways, and it’s obvious they are thinking something like us too.

I am not saying they are as good as us yet, though, for a few small reasons and one big one.

The Limitations

Current frontier “thinking” models are not AGI in the modern definition. They can’t do every task humans can do intellectually (IE without a body, which I will get to) for several reasons:

-

Looping/Recursive reasoning: This was a huge problem for early transformers that had to output in one shot, and the examples were obvious. This one has been essentially solved via thinking models like o1, and now o3, gemini and grok thinking models, and many more. That was a huge unlock and a huge boon for applications like programming where there is lots of nested recursion of logic that has to occur to find a reasonable solution.

-

Memory and context: Context windows get larger all the time, but this limitation still is not solved. Just adding a bunch of tokens into a context window doesn’t get you much when 2 million token models lose coherence after about the first 40,000 - which they do, and which every programmer working with anything but a tiny codebase intuitively understands. But this one too will largely be solved soon, if not through architectures that actually update their weights, it’ll be solved through nuanced memory systems that people are actively developing on top of thinking models.

-

Size: This is basic, but most of the models we can interact with today are still working with an order of magnitude fewer neural synapses than human brains. It could very easily be that, even with the other problems solved, we just need bigger electronic brains to match the size of our meat ones. It certainly feels like some of the ways LLMs fail today sort of come down to “not enough horsepower” types of issues.

-

Vision: And this one might sound funny to someone that is paying attention to AI in particular, because GPT-4 with vision launched something like 2 years ago now. And it has been impressive for a long time, able to do things like identify what objects are in an image, where an image is from, etc: things most humans can’t do glancing at an image, that seem super-human.

But the vision itself is not “good” vision. It cannot really pick out small important details, and it still behaves in many ways like vision recognition models have for years now. Now that we have a model that has both thinking and image input and editing at every step, the o3 and o4-mini series that recently released, we can really start to see the limitations in vision. Let me take you through 2 examples that represent the 2 types of failure modes that result from these not having true image understanding, yet.

My thesis today is that this is the key limitation that is not going to be overcome “by default,” but that it will be overcome.

Proof the Vision is Not There Yet

Each release from the major providers steadily knocks away my intelligence tests, which I admit are mostly programming oriented, but the ones that they can never really dent are the spatial reasoning ones - where a model really has to think about images in its head or use an image provided for detailed work.

Simple 3D Modeling with Frontier AI Models

Every major model release, I test what models can do with OpenSCAD. I won’t get technical about it here, but OpenSCAD is a CAD program (Computer Aided Design - think 3D modeling for engineers, not the artistic kind) that is defined entirely through a programming language vs the typical mouse strokes and key presses that software like SolidWorks or AutoCAD depend on.

This makes OpenSCAD the perfect test platform for a model that inputs and outputs text primarily. I can describe a 3D model I want, and the model can output text that renders into a 3D model.

As amazing as LLMs are at scripting in normal programming languages, they have never been good at OpenSCAD. See my link above for GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 trying to model an incredibly simple object. That acorn was about as complex as GPT-4 could get without really falling down.

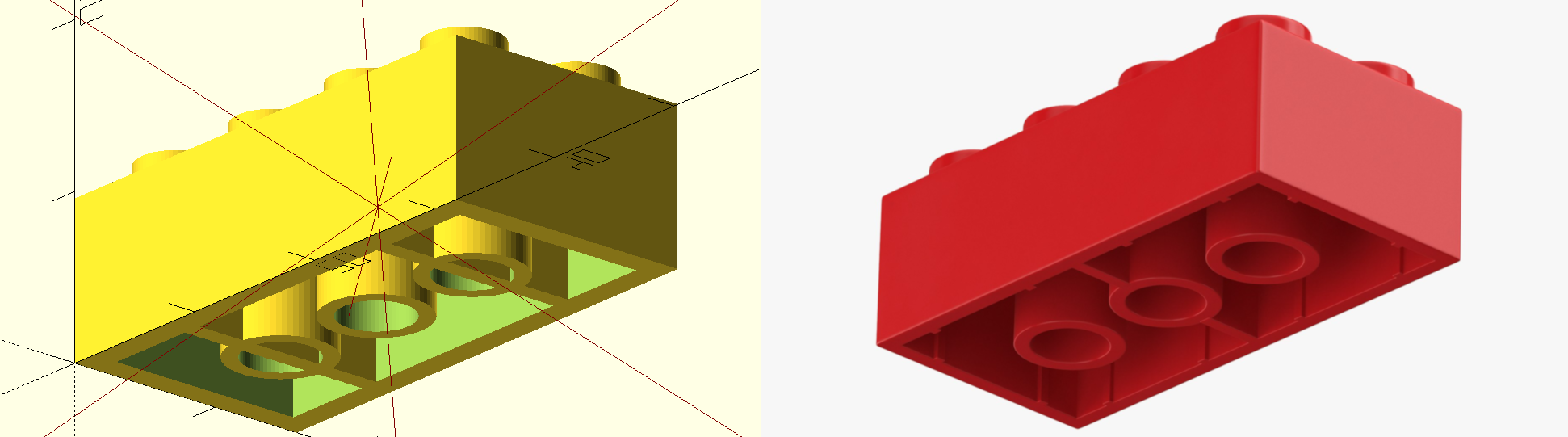

Here is OpenAI’s o3’s attempt to make a standard 2x4 Lego Brick:

o3's model left, real Lego brick right

o3's model left, real Lego brick right

This was the easiest object I tested, and o3 does a decently good job. It grabbed the correct dimensions online and, using its inherent training data of what a 2x4 Lego block is, applied those dimensions into a mostly coherent object. It has one major flaw, which you can see on the underside as I have the image rotated - it drew two lines through two of the cylinders. My guess is that this is its interpretation of the supports in the middle of the actual Lego brick, that connect but don’t run through the center cylinder.

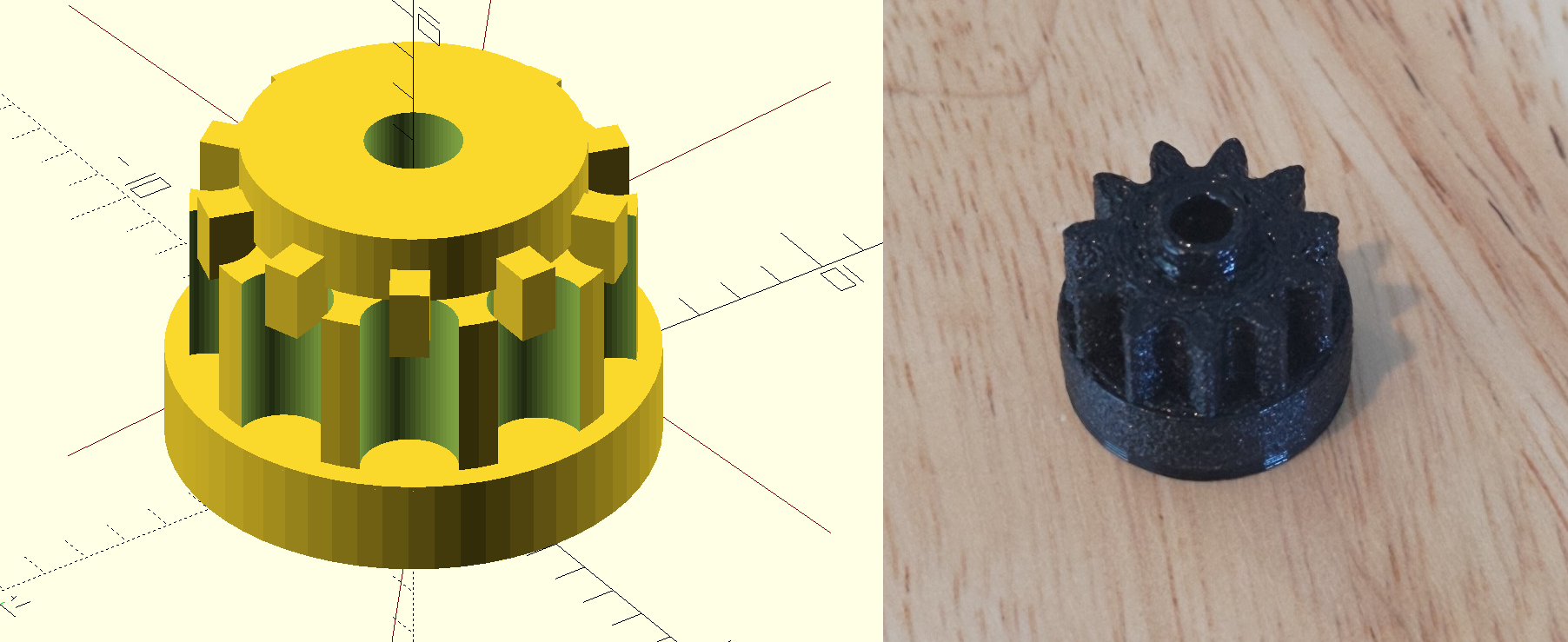

Now for a harder test: a simple engineering part that’s definitely not in its training data, because it is my own design. I printed this for a robotics project more than a decade ago, and had it sitting around in my 3D printer storage drawer.

It’s a bit of a weird part - a pinion with a smooth section and an 11-tooth gear of equal diameter, and a hole in the center with a slightly raised wall. This is the kind of part that an engineer well versed in AutoCAD or SolidWorks can produce in just a few minutes, but which requires attention to detail and a conceptual model of how parts fit together.

o3's model left, real part right

o3's model left, real part right

This is where you can see how these models fall apart. o3 immediately gets that it’s a pinion, that it has a hole in the middle, and that it has a smooth section on the bottom and a gear on top. But the execution is nowhere close to workable, from most major to least (in my opinion):

- There are two gears (unknown as to why or if this is intentional, o3 explained one as a “grooved ring” - whatever that means)

- The gear teeth are concave - whereas the rounded sharp tooth shape is clear in the image

- There are 10 teeth, not eleven - which seems trivial, but it’s indicative of a real flaw that messes up all complex models I throw at AI - where LLMs make an assumption like what number of teeth is “likely,” rather than looking at the image in detail and counting them.

- There is clearly an attempt at the raised wall around the top hole, but it’s far too big.

- The height of the smooth base section and gear sections are equal in the real part, but o3 makes the gear more than 3x thicker than the base.

Map Reading

Here’s another great example of what I mean when I say that frontier models have bad vision.

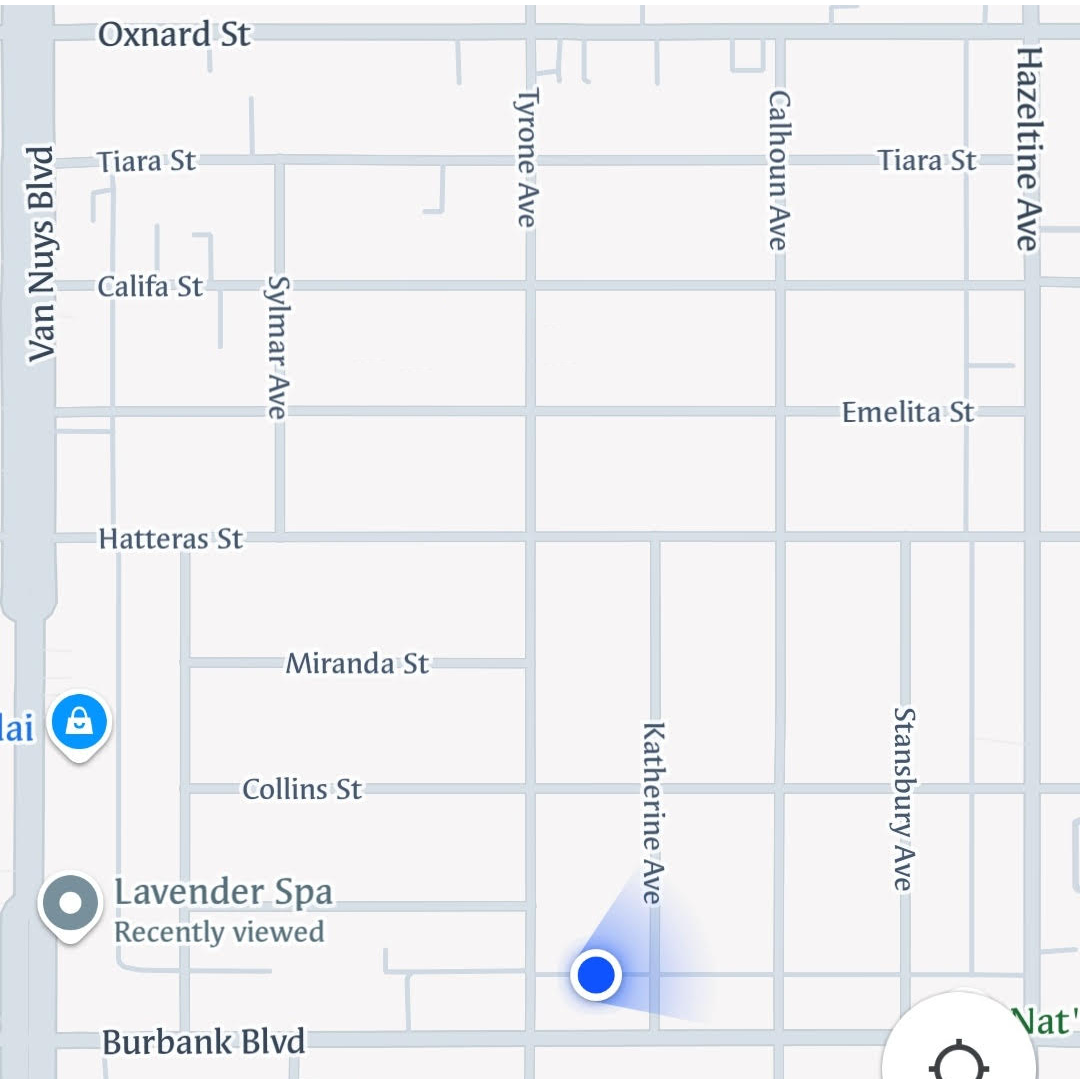

I recently gave this question to the latest thinking image model, o3: “Here’s an image from Google Maps of the block I live on between the avenues of Burbank, Hazeltine, Oxnard, and Van Nuys. What is the longest continuous loop I can walk within the neighborhood without crossing my path or touching one of the avenues? This square is 1/2 mi on each side”

The image uploaded with this query

The image uploaded with this query

O3 thinks for 4 minutes about this question, zooming in to various parts of the map countless times to form the route. And then it fails on the first step, suggesting starting at Tiara and Stansbury, which do not intersect on the map. Any person looking at this image could tell that is true in just a few seconds.

This is what I mean when I say these things have bad vision - and this is the best model from the lab I think has the best vision. Vision is not about being able to identify millions of different objects, ImageNet-style. It’s about seeing the detail and paying attention to the right thing. Here in this map, that means looking roughly at the lines representing Stansbury and Tiara, looking at where they would intersect, and seeing they do not.

Though getting AI models to read maps and create 3D models from code may not be on everyone’s rubric, any UX developer that has worked with a frontier AI knows what I’m saying intuitively. This is likely just as true for any role heavily leaning on visual information. There is a difference between generating some Tailwind code that spits out a standard UI and getting to the level of complexity that the AI starts to need to look at screenshots in detail and know the relative position and orientation of components, or see small details. They just.. don’t do that yet.

Non-Frontier AI Models

A common retort to this argument might be “Well Brian, you’re using the wrong type of model.”

But believe me, I try essentially everything I can get my hands on, and like non-LLM AI models in other domains, other than being incredibly limited in application, these models are simply not good at vision, either. Here’s an image of a 3D model generated by Zoo CAD, a company doing text and image to 3D, which was, when I printed it back in January at least, state of the art in this domain:

My Flipper Zero (left) and its 3d-printed clone (right)

My Flipper Zero (left) and its 3d-printed clone (right)

The input to the model was a picture I took of my Flipper Zero hacking toy. The 3D print on the right is of the 3D model it produced, with the only modification on my part being to scale it.

I have long awaited an easy way to “3D scan” parts from the real world into software. This would make so many of my DIY printing jobs around the house much easier - and it gets us one step closer to the dream of teleportation.

And I was impressed when I first saw this output - it was one of the best of my attempts with this AI tool. Feature-wise, it did a pretty good job of capturing the main facets of my Flipper Zero. But it’s just too obviously not good enough: dimensions are all wrong, there is hallucinated symmetry all over the place, and small details are missed everywhere. One of the reasons I printed this model was just to get a real feel for how similar it is to the Flipper when scaled correctly, and it just becomes obvious that this is not a useful technology yet when you hold both of them in your hands.

My prediction is that frontier models will get there before purpose-trained models like the one that cloned my Flipper Zero. This has been the reality across most other domains of AI. Now that we have general-purpose AI models that have started to encapsulate a working, if not complete, conceptual model of the world, they are starting to outperform all of the smaller purpose-built models of the last decade.

And this will be good for the general capability of the AI industry: It’s a much better outcome to have a few general-purpose models that can do fine visual work, that can be prompted and orchestrated by people working in different domains, than it is to need an AI lab or startup to train a specific model for every task. It’s the same reason I believe humanoid robots are going to win over purpose-built ones in the long run: We can’t predict what users will want their robots to do, and our world is built for humans to operate in it - therefore the most capable robots will be shaped generally like humans.

So how will frontier models get good at visual tasks, if they have such bad vision right now? I think the answer to that question also involves humanoids.

The Humanoids

What I think is going on in these examples of frontier model vision failures is that we have a limitation in training data (duh!) - but that isn’t because there aren’t a lot of images and videos on the internet, it’s because there is so much more information in the average image than there is in the average chunk of text, and a lot more of that information is irrelevant to any given question.

When I say that we have a limitation on training data, I’m not in the typical camp of “well, then transformer neural nets are obviously stupid because I was able to understand this thing without training on terabytes of data from the internet”. This has always been a bad take because the average human trains on petabytes, not terabytes of data, and that data is streamed into their brains mostly in the form of images. I am also not in the camp of thinking that this means that the data “just doesn’t exist” to get these models to AGI in the visual dimension. It so clearly does exist, and it exists so abundantly that a unique image stream can be sent to each of the billions of human brains, and they all learn the same principles that let them immediately identify the mistake that the cutting-edge thinking vision model made after 4 minutes of rigor.

Not only does the data exist: We never actually had a data problem in AI in the first place. We have an instruction problem. That doesn’t mean model architecture or data massaging really, it means that we need to plug our models into the real world where all the data streams exist. I believe this will come first in the form of robots with cameras on them, the first of which is happening en masse via Tesla full self-driving AI, and I’m sure those vision neural nets are quite insanely capable compared to what we see in the consumer transformer vision models. But the real leap probably comes when we get to humanoid robots walking around collecting and learning from vision data every day - and learning from actions they take in the real world.

If you’ve ever tried to get concrete actions to take based on a vision-transformer’s outputs, you will know it’s hard. I never posted about it, but I did a small project with a friend a year or two ago, trying to get automated QA working on web software, and we failed in a lot of different ways. I am very impressed that the big labs are starting to crack computer use - because getting an LLM to give specific coordinates or elements to click on is the same type of challenge I was testing above. But it’s no wonder these computer use applications are still very inaccurate.

Letting transformer-based agents control robots will be a much harder problem of a similar type. Not only does it require attention to detail, but now the images are in 3D, they come at you many times per second, and actions need to be produced as quickly. But my prediction is that we will brute force this, and it will work “well enough” for enthusiasts and niche industrial use cases to benefit from humanoid robots. And that’s the takeoff point for true vision, as we all intuitively understand it. Releasing humanoids at scale (and cars, to some extent) are when we really unleash the datastream that’s needed to get models that can see as well as you or I can. This is probably one reason why many AI companies and labs are pushing them so hard - they also understand the data they collect will be more valuable than the money paid for the first units.

Once we have a few hundred thousand humanoids roaming around early adopters’ houses, we will start to see AI models that can use OpenSCAD and Google Maps. And, conveniently, that’s also the missing capability that will make the humanoids really useful. We have interesting years ahead of us.

200

200